LINK to Jon Sundell workshop flyer: Teaching Children to Tell Stories

LINK to sample workshop activities to introduce storytelling and teach storytelling skills. (Steps 2 & 5)

LINK to a four minute documentary video excerpt of children learning to tell stories. After clicking on this link, scroll down to Children Tell Stories: Teaching and Using Storytelling in the Classroom, by Martha Hamilton and Mitch Weiss, then click on on 2nd link in book's description.

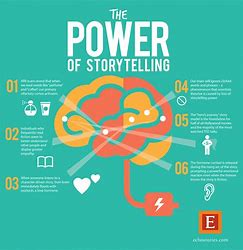

Over the past five decades hundreds of research studies have demonstrated the educational benefits of stories and storytelling. Kendall Haven's groundbreaking book, Story Truth: The Science Behind the Startling Power of Story, which is cited several times here, was based on the findings of over 350 studies! I have drawn from those and many others to map out an organized schema of testimonies. Sixty-five excerpts in fourteen categories testify to multiple ways in which students benefit from stories and, especially, storytelling. In addition to classifying the benefits, I have also used bolded and underlined text to make them easier to skim and navigate.

I have included so many testimonies (although they represent at most 15% of what is available) in order to to emphasize how overwhelming is the research that has been done, although I think few educators realize this. There is more than enough evidence here to clearly demonstrate the enormous potential that stories and storytelling hold for intellectual, social and emotional learning. Furthermore, Haven's work and many of the smaller studies attest that amid the great power of stories, the greatest impact is felt through storytelling; and within that realm the ultimate experience is not only listening to but telling stories. In recent years the world of business has recognized and widely utilizes the power of storytelling to communicate its messages. Haven and an increasing number of educators are asking why the field of education has generally paid so little attention to this powerful tool. I hope this information can increase awareness and utilization of its tremendous potential to make the learning process broader, deeper, more fruitful and exciting.

![storytelling-painting[1] simplicityparenting.com storytelling-painting[1] simplicityparenting.com](https://songsandtales.com/wp-content/uploads/storytelling-painting1-simplicityparenting.com_-1.png)

Before delving into the detailed catalog of excerpts, I have set out four short overviews that delineate specific connections of teaching storytelling to school curriculum: (1) summary of impact on literacy and social emotional learning; (2) application to 21st century learning skills; (3) connections to North Carolina educational standards; (4) value as culturally responsive pedagogy.

Information in this first section is mainly drawn from Children Tell Stories: Teaching and Using Storytelling in the Classroom, with a few additions and elaborations by myself. Based on decades of personal experience, this manual by Martha Hamilton & Mitch Weiss, known collectively as Beauty and the Beast Storytellers, is a thorough and thoughtful guide to both the value and procedures of teaching this powerful skill to children.

LITERACY SKILLS DEVELOPED

- Both telling and listening to stories instill a sense of joy in language and words that makes children want to read.

- Listening to and telling stories stimulate the powers of imagination and visualization, which are keys to comprehension and higher order thinking.

- In telling stories students develop their oral communication skills, which are a critical tool for real world success.

- Students who struggle with writing can build on oral language strengths to improve their writing skills.

- As student storytellers dramatically consider and convey plot, characters and emotions to an audience, they develop a visceral understanding of story structure, which increases their reading comprehension skills.

SOCIAL EMOTIONAL DEVELOPMENT

- Through learning and sharing tales, then coaching each other in a positive manner, a class develops a spirit of community and cooperation.

- Stories build empathy in students as they are drawn into and emotionally experience the fictional lives of characters.

- Folktales teach about compassion, courage, honesty and other important qualities in an accessible and compelling way that helps children build stronger character.

- Students increase their confidence and self-esteem as they work to develop a story, then receive positive attention from peers.

- As they read, learn, tell and listen to international folktales, students expand their appreciation of different cultures, as well as pride in their own background.

TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY LEARNING SKILLS

- Creativity and critical thinking are obviously essential to creating a dramatic life tale out of one's personal memories and insights. Less obviously, they are also essential to the process of taking a traditional folktale, generally encountered in a written form, and developing it into a dynamic oral presentation. In our story teaching process the teller finds his own language, voicing, pacing and physical expression to accentuate emotion, character and plot development.

- Communication skills, especially oral ones that do not get a lot of emphasis in our normal school curriculum, are obviously developed as students strategize, practice and perform their tales.

- Flexibility is developed as students learn to adapt their telling to the response of each audience in this two-way communication process.

- Collaboration is key as the students encourage and direct their fellow tellers in this group process of learning and preparing tales.

- Social skills are honed in a variety of ways, through the collaborative process and also through story listening, as detailed above and below in sections 3 & 4 of the detailed documentation.

PRINCIPAL NC EDUCATIONAL STANDARDS (GR 3-5) TAUGHT AS STUDENTS LEARN TO TELL STORIES

Many additional standards are addressed in this undertaking. However, these are the major ones involved.

READING: LITERATURE

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.3.2 - Recount stories, including fables, folktales, and myths from diverse cultures; determine the central message, lesson, or moral and explain how it is conveyed through key details in the text.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.3.3 - Describe characters in a story (e.g., their traits, motivations, or feelings) and explain how their actions contribute to the sequence of events

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.4.3 - Describe in depth a character, setting, or event in a story or drama, drawing on specific details in the text (e.g., a character's thoughts, words, or actions).

WRITING:

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.3.3, 4.3, 5.3 - Write narratives to develop real or imagined experiences or events using effective technique, descriptive details, and clear event sequences.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.3.3.A, 4.3A, 5.3A - Establish (or orient the reader by establishing) a situation and introduce a narrator and/or characters; organize an event sequence that unfolds naturally.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.3.3.B; 4.3B - Use dialogue and descriptions of actions, thoughts, and feelings to develop experiences and events or show the response of characters to situations.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.5.3.B - Use narrative techniques, such as dialogue, description, and pacing, to develop experiences and events or show the responses of characters to situations.

SPEAKING & LISTENING:

- CCSS: ELA-LITERACY - SL.3.4 - Report on a topic or text, tell a story, or recount an experience with appropriate facts and relevant, descriptive details, speaking clearly at an understandable pace.

- CCSS: ELA-LITERACY - SL 4.4 - Report on a topic or text, tell a story, or recount an experience with appropriate facts and relevant, descriptive details, speaking clearly at an understandable pace. Adjust speech as appropriate to audience.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.5.6 - Adapt speech to a variety of contexts and tasks, using formal English when appropriate to task and situation. (See grade 5 Language standards 1 and 3 here for specific expectations.)

SOCIAL STUDIES

- 4, 5. B.1 Understand ways in which values and beliefs have

influenced the development of North Carolina and the United States. - 4, 5. B.1.1 Explain how traditions, social structure, and artistic expression have contributed to the unique identity of North Carolina and the United States

CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE PEDAGOGY

Culturally responsive pedagogy is a student-centered approach to teaching in which the students’ unique cultural strengths are identified and nurtured to promote student achievement and a sense of well-being about the student’s cultural place in the world. (Matthew Lynch. What is Culturally Responsive Pedagogy? Theadvocate.org April, 2016) Storytelling is an excellent tool for incorporating this approach in the classroom. It does this in several different ways.

1. Folktales affirm the importance of students' cultural roots. They spring directly from the diverse cultures of which our students are a part, representing attitudes, experiences and values of their heritage. In fact, many of those tales have served traditionally as a means of teaching those values, and students may hear the voices of their parents and grandparents in them. Consequently, when students read, hear and, especially, tell these stories, they are likely to feel a sense of pride. As a bilingual storyteller, I have often had teachers and principals remark after my programs that they saw their Hispanic students, who often feel personally and culturally inferior in school, sitting taller and prouder when I shared a story or song from their culture.

2. Students feel represented as they go through the process of selecting a story that speaks to them. In learning to tell their story students are encouraged to make it their own, using words and physical expression that feel natural to them. This helps promote a sense of ownership - of the story and the culture it springs from.

3. As students create and tell life stories, they apply and validate their personal experiences. Immigrant children of first or second generation frequently write and speak about situations related to their own and their families' cultural identity.

4. Extended storytelling workshops generally culminate in a performance for the students' family and friends. this provides yet another opportunity for the students to feel a sense of personal and cultural pride.

DETAILED DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH STUDIES

Below are sixty-five excerpts and summaries from research studies, articles, personal anecdotes and books testifying to and documenting the educational impact of storytelling. Thanks to the following people and organizations for leading me to these sources: Donald Davis, renowned North Carolina storyteller and writer, who has articulated and extensively explored the link between oral and written language; Marilee Clark, of the Timpanogos Storytelling Festival in Provo, Utah; the National Storytelling Network, whose "storytell" listserve put me in touch with the following people: Dr Eric Miller of the World Storytelling Institute in Chennai, India; Richard Marsh, whose blog, "Richard Marsh, Bardic Storyteller," has an extensive "Storytelling in Education" page; Margaret Read MacDonald, prolific storyteller, story collector, and author, who directed me to her excellent teacher's guide, Teaching with Story: Classroom Connections to Storytelling.

MENU

1. Introduction: General Comments on Educational Benefits

2. Brain Research - Neurological Impact of Stories 3. Stories Build Social Skills 4. Stories Build Empathy and Reduce Prejudice

5. The Importance of Oral Language

6. Oral Skills Help Develop Writing Skills

7. Motivating and Helping Struggling Readers & Learners/ Appealing to Multiple Intelligences

8. Growing the Imagination, Creativity, and Higher Order Thinking Skills

9. Story Structure & Content Assist in Memory

10. Stories & Storytelling Increase Reading Comprehension

11. Story-telling Is the Most Impactful Story Presentation Form

12. The Ultimate Gain: Students Telling Stories

13. Storytelling Helps English Language Learners

14. Story-listening Prepares Preschoolers for Reading

15. Conclusion - Teaching Storytelling: Position Paper from National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE)

1. GENERAL COMMENTS ON EDUCATIONAL BENEFITS

“Children’s hunger for stories is constant. Every time they enter your classroom, they enter with a need for stories. Wright, A. Storytelling with children. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

"Children process the world in story terms, using story as a structure within which to create meaning and understanding.” Haven, Kendall. Story Proof: The Science Behind the Startling Power of Story. Westport: Libraries Unlimited, 2007.

"Statistics provided to me privately by a storyteller conducting sessions for 10-12-year-olds at least twice a month in a town in the United States compare results of tests in reading assessments and oral fluency between groups exposed and not exposed to regular storytelling. These figures, covering the years 2011-2014, show that the story group improved by at least 50% and often more than 100% over the school year. Even more relevant is that the students this teller worked with were “the most troubled, low-achieving students in the grade level”. This small, unofficial study accurately reflects the anecdotal reports of storytellers in schools everywhere." Marsh, Richard, bardic storyteller. Storytelling in Education blog.

“The relationship of storytelling and successful children’s literacy development is well established.…This process (storytelling) enhanced children’s development of language and logic skills.” Cliatt, M., and J. Shaw. "The Storytime Exchange: Ways to Enhance It." Childhood Education, 64(5), pp. 293-298, 1988.

“Stories enhanced recall, retention, application of concepts into new situations, understanding, learner enthusiasm for the subject matter.” … Stories enhanced and accelerated virtually every measurable aspect of learning.” Coles, R. The Call of Stories: Teaching and the Moral Imagination. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1989.

“Storytelling has demonstrable, measurable, positive, and irreplaceable value in teaching.” Schank, R. "Every Curriculum Tells a Story." Tech Directions, 62(2), pp. 25-29, 2000.

“Recently the efficacy of early reading and storytelling exposure has been scientifically validated. It has been shown to work.” Snow, C., and M.Burns, eds. Preventing Reading Difficulties in Young Children. Washington, ton, DC: National Research Council and National Academy Press, 1998.

“New Jersey storyteller Susan Danoff is executive director of a nonprofit company providing in-class storytelling programs to inner-city schools. Her programs involve repeat visits to each participating classroom. Over an eight-year period, she collected almost 1,000 Teacher Observation Sheets describing behavioral or academic performance changes the teacher noted that the teacher felt were caused by, and should be credited to, the storytelling program. These sheets covered pre-kindergarten through fifth grade. More than half of the teachers credited storytelling with increasing attention span or helping students learn to pay attention. Almost half noted that overactive children learned to sit still and listen through storytelling. Academically, two-thirds of all teachers credited storytelling with improving student comprehension skills…Ninety-three percent of kindergarten teachers said that the program improved their students' verbal skills. More than 70 percent of other grade teachers agreed. Half of all teachers (kindergarten and above) believed that storytelling significantly improved student writing skills (including two-thirds of intermediate grade teachers.) More than 75 percent of these same teachers said that the storytelling program improved their students' critical thinking and general imagining and envisioning skills. These are all anecdotal teacher observations. Yet the consistency and acclaim evident in these results is startling. A one-hour, once-a-week (in some cases only once-a-month) storytelling program had a major and lasting impact on student behavior and language arts achievement.” Haven, Kendall. Story Proof: The Science Behind the Startling Power of Story, Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited, 2007.

“New Jersey storyteller Susan Danoff is executive director of a nonprofit company providing in-class storytelling programs to inner-city schools. Her programs involve repeat visits to each participating classroom. Over an eight-year period, she collected almost 1,000 Teacher Observation Sheets describing behavioral or academic performance changes the teacher noted that the teacher felt were caused by, and should be credited to, the storytelling program. These sheets covered pre-kindergarten through fifth grade. More than half of the teachers credited storytelling with increasing attention span or helping students learn to pay attention. Almost half noted that overactive children learned to sit still and listen through storytelling. Academically, two-thirds of all teachers credited storytelling with improving student comprehension skills…Ninety-three percent of kindergarten teachers said that the program improved their students' verbal skills. More than 70 percent of other grade teachers agreed. Half of all teachers (kindergarten and above) believed that storytelling significantly improved student writing skills (including two-thirds of intermediate grade teachers.) More than 75 percent of these same teachers said that the storytelling program improved their students' critical thinking and general imagining and envisioning skills. These are all anecdotal teacher observations. Yet the consistency and acclaim evident in these results is startling. A one-hour, once-a-week (in some cases only once-a-month) storytelling program had a major and lasting impact on student behavior and language arts achievement.” Haven, Kendall. Story Proof: The Science Behind the Startling Power of Story, Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited, 2007.

“Once we recognize story structure as a prominent feature of human understanding, then we are led to re-conceive the curriculum as the set of great stories we have to tell children and recognize elementary school teachers as the storytellers of our culture.” Egan, Kay.The Educated Mind: How Cognitive Tools Shape Our Understanding, University of Chicago Press, 1997.

NATIONAL COUNCIL OF TEACHERS OF ENGLISH Position Statement on Teaching Storytelling- full text. Click link here

Or you can find the position statement at the conclusion of the detailed documentation.

2. BRAIN RESEARCH - NEUROLOGICAL IMPACT OF STORIES

“A recent brain-imaging study reported in Psychological Science reveals that the regions of the brain that process sights, sounds, tastes, and movements of real life are activated when we’re engrossed in a compelling narrative. That’s what accounts for the vivid mental images and the visceral reactions we feel when we can’t stop reading, even though it’s past midnight and we have to be up a dawn. When a story enthralls us, we are inside of it, feeling what the protagonist feels, experiencing it as if it were indeed happening to us, and the last thing we’re focusing on is the mechanics of the thing.” Cron, Lisa. Wired for Story: The Writer’s Guide to Using Brain Science to Hook Readers from the Very First Sentence. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press, 2012.

“A recent brain-imaging study reported in Psychological Science reveals that the regions of the brain that process sights, sounds, tastes, and movements of real life are activated when we’re engrossed in a compelling narrative. That’s what accounts for the vivid mental images and the visceral reactions we feel when we can’t stop reading, even though it’s past midnight and we have to be up a dawn. When a story enthralls us, we are inside of it, feeling what the protagonist feels, experiencing it as if it were indeed happening to us, and the last thing we’re focusing on is the mechanics of the thing.” Cron, Lisa. Wired for Story: The Writer’s Guide to Using Brain Science to Hook Readers from the Very First Sentence. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press, 2012.

“Many scientists now believe we have neural networks that activate when we perform an action or experience an emotion, and also when we observe someone else performing an action or experiencing an emotion. This might explain why mental states are contagious…..

"Mirror neurons may also be the basis of our ability to run powerful fictional simulations in our heads. A pioneer of mirror neuron research, Marco Iacoboni, writes that movies feel so authentic to us because mirror neurons in our brains re-create for us the distress we see on the screen. We have empathy for the fictional characters—we know how they’re feeling—because we literally experience the same feelings ourselves. And when we watch the movie stars kiss on screen? Some of the cells firing in our brain are the same ones that fire when we kiss our lovers. ‘Vicarious’ is not a strong enough word to describe the effect of these mirror neurons.

"Mirror neurons may also be the basis of our ability to run powerful fictional simulations in our heads. A pioneer of mirror neuron research, Marco Iacoboni, writes that movies feel so authentic to us because mirror neurons in our brains re-create for us the distress we see on the screen. We have empathy for the fictional characters—we know how they’re feeling—because we literally experience the same feelings ourselves. And when we watch the movie stars kiss on screen? Some of the cells firing in our brain are the same ones that fire when we kiss our lovers. ‘Vicarious’ is not a strong enough word to describe the effect of these mirror neurons.

"We know from laboratory studies that stories affect us physically, not just mentally." Gottschall, Jonathan. The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human. New York: Mariner Books, 2012. Pg. 60-61

“Storytelling is crucial to child development, and helps to strengthen neural pathways that make learning of all kinds possible. Chilton Pearce, in his book Evolution's End, asserts that the repeated exposure to stories and the subsequent triggering of mental images …causes neural pathways to form and strengthen within the brain, and the strengthened connections between the different parts of the brain allow the child to more easily incorporate additional learning.” Fredericks, Linda. Developing Literacy Skills Through Storytelling,”The Resource Connection, Spring, 1997

3. STORIES BUILD SOCIAL SKILLS

Humans also respond to stories because they allow us to explore the benefits and consequences of different outcomes through the choices of their characters. In turn, this enhances our ability to plan and succeed in our own lives. Firth, Perry. "Wired for Empathy: Why We Can’t Resist Good Narrative." firesteelwa.org. July 16, 2015.

Stories provide a simplified simulation world that helps us make sense of and learn to navigate our complex real world. The aspects of our real world that are usually most challenging, most crucial for us to understand, are social aspects. Knowing how to deal with evil as well as love, how to recognize others’ desires and needs, how to behave towards others so as to retain their friendship, and how to earn the respect of the larger society are among the most important skills we all must develop for a satisfying life. Stories that we like, and that our children like, are about all that. They are not explicitly about how to navigate the social world, in the way that a lecture might be. Rather, they are implicitly about it, so listeners or readers have to construct the lessons for themselves, each in his or her own way. Constructed lessons are far more powerful than those that are imparted explicitly.

When we enter into a story we enter a make-believe world where, precisely because it is make-believe and has no immediate real-world consequences, and because the events are simplified and the important ones made salient, we can experience the challenges and difficulties more clearly, think about them more rationally, and develop more insight about them, then we might from real-world experience. Gray, Peter, Ph. D. "One More Really Big Reason to Read Stories to Children." Psychologytoday.com. Oct. 11, 2014.

4. STORIES BUILD EMPATHY AND REDUCE PREJUDICE

Other researchers have pointed out how stories facilitate the development of “theory of mind” and empathy. “Theory of mind” is a term for how humans intuit/understand the mental states of others. It is part of the ability to “walk in another person’s shoes,” and also informs the thoughts and choices we make in our own lives. Firth, Perry. "Wired for Empathy: Why We Can’t Resist Good Narrative." firesteelwa.org. July 16, 2015.

Because listening or reading is mentally active but physically passive, it promotes thought and reflection that may not occur so much in real life. In real life, the drive to action, or the stress induced, or the ego defenses that are raised, may shortcut reflection. But in fiction, where we cannot alter what happens, all we can do is feel, reflect, and think. In the process we may learn to care about people whom we might not otherwise care so much about, including people who are quite different from ourselves. Gray, Peter, PHD. "One More Really Big Reason to Read Stories to Children." Psychologytoday.com. Oct. 11, 2014.

In an experiment conducted in a low-income area of Toronto, the capacity of 4-year-olds to take another person’s perspective and reason from that perspective increased greatly as a result of an intervention in which they heard many stories read to them by parents, teachers, and research assistants. Joan Peskin & Janet Wilde Astington (2004). "The effects of adding metacognitive language to story texts." Cognitive Development, 19, 253-273.

Another study found that second-grade students who read stories featuring black and other racial minority children were more likely to include black children in their own social group and reported more positive views of black people, than children who read stories with white main characters. John H. Litcher & David W. Johnson (1969). "Changes in attitudes toward negroes of white elementary school students after use of multiethnic readers." Journal of Educational Psychology, 60, 148-152.

5. THE IMPORTANCE OF ORAL LANGUAGE

5. THE IMPORTANCE OF ORAL LANGUAGE

Oral language is an important tool for the cognitive growth of young children.

Van Groenou, M. “Tell me a story”: Using children’s oral culture in a preschool setting. Montessori LIFE 1995, Summer.

Oral and literate are not opposites; rather, the development of orality is the necessary foundation for the later development of literacy…. Indeed, a sensitive program of instruction will use the child’s oral cultural capacities to make reading and writing engaging and meaningful. Egan, K., Literacy and the oral foundation of education, The NAMTA Journal, 18, 1993, Winter 11-46.

"One area reading researchers agree on is that oral language competencies are essential in literacy development. Storytelling requires listening and visualization - key oral language and comprehension competencies and strategies. It also provides vocabulary development, in context." Gangi, Jane M. Associate Professor, Department of Education, Sacred Heart University, Fairfield, CT. Encountering Children’s Literature: An Arts Approach. Pearson (Allyn and Bacon), 2004.

6. ORAL SKILLS OF STORYTELLING HELP DEVELOP WRITING SKILLS

“Children at any level of schooling who do not feel as competent as their peers in reading or writing are often masterful at storytelling. The comfort zone of the oral tale can be the path by which they reach the written one. Tellers who become very familiar with even one tale by retelling it often, learn that literature carries new meaning with each new encounter. Students working in pairs or in small storytelling groups learn to negotiate the meaning of a tale.

“Writing theorists value the rehearsal, or prewriting, stage of composing. Sitting in a circle and swapping personal or fictional tales is one of the best ways to help writers rehearse.”Teaching Storytelling: Position Statement from the Committee on Storytelling, National Council of Teachers of English, 1992

Whitman, Nathaniel. " A Study of Storytelling's Effect on Primary (7-9 year old) Writing." M. Ed. Thesis, University of Western Australia, 2006. Hong Kong International School second graders were given writing prompts. The first week they were given a prompt and then began to write immediately. A week later, after a different prompt, they were given a chance to tell their story to a partner before writing. The writing produced after storytelling was used as a pre-writing exercise showed more sophisticated sentence structure, a higher degree of organization, and a stronger word choice in their final, written work. MacDonald, Margaret Read. Teaching with Story: Classroom Connections to Storytelling. Atlanta: August House, 2013.

Gebracht, Gloria Jean. "The Effect of Storytelling on the Narrative Writing of Thrid-grade Students." Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 1994. Ninety-four third-grade students inf our classes wee given pre-and post-tests for writing skills. After listening to stories, significant gains were made in story composition and in oral storytelling skills. Greatest effect was had on the below-average readers. Teaching with Story: Classroom Connections to Storytelling. Atlanta: August House, 2013.

7. MOTIVATING AND HELPING STRUGGLING READERS & LEARNERS/ APPEALING TO MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCES

“Telling young children stories  motivates them to read. Elementary school teachers have found that even students with low motivation and weak academic skills are more likely to listen, read, write and work hard in the context of storytelling.” What Works About Teaching and Learning, US Department of Education, 1986

motivates them to read. Elementary school teachers have found that even students with low motivation and weak academic skills are more likely to listen, read, write and work hard in the context of storytelling.” What Works About Teaching and Learning, US Department of Education, 1986

The importance of fostering motivation for reading and learning cannot be underestimated. Skills and worksheet-driven classrooms cannot teach or motivate, as storytelling can, the love of language, stories, characters, and ideas. Nor can they, as storytelling can, foster curiosity. Gangi, Jane M, Associate Professor in the Department of Education at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, CT, author of Encountering Children’s Literature: An Arts Approach. Pearson (Allyn and Bacon). 2004.

"One more voice for the power of storytelling to reach students identified with various learning challenges. Liz and I are back at the pueblo school where we’ve been doing residencies for almost 10 years now. This year the terms of the contract are a little different and we are mainly working with kids with various challenges that cause them to struggle with reading, writing, comprehension, etc. Not surprisingly, because we’ve seen this again and again… most of these kids “take” to stories and often astonish their teachers with their recall, ability to remember, or retell stories… we’ve got students who haven’t heard a story in a year or more… stories we’ve forgotten we even know, that they can tell. It’s probably pretty obvious and we certainly don’t have any research to back it up… but one factor undoubtedly is that hearing and working with stories is inherently fun… whereas “language arts” for those who struggle to read, write etc, is inherently stressful. Imagine that…some kids learn better when they are having fun."

Bob Kanegis, storyteller, United States

“Children at any level of schooling who do not feel as competent as their peers in reading or writing are often masterful at storytelling. The comfort zone of the oral tale can be the path by which they reach the written one. Teaching Storytelling: Position Statement from the Committee on Storytelling, National Council of Teachers of English, 1992

"As a storyteller with dyslexia and dyscalculia, I can assure you that storytelling is key to a positive learning experience. While most of us with these issues seem to be reasonably intelligent, in the past we were often shunted into situations – well-meant, where our needs could not be adequately addressed. Because of this, I applaud the storytelling approach in the classroom as it is inclusive. Oral storytelling releases something essential, allowing us to embrace meaning, color, expression and imagination; it is liberating for those of us marching to a different beat.

"When one is purely wired for learning through story, the classroom with all its confusing stimuli can be an intimidating experience. Storytelling’s one-on-one transmission can be miraculous, calming all the jangled nerves and allowing focus. Something literally settles as the mind automatically links into the information being provided. It is both a physical experience and an emotional one." Saundra Kelley, storyteller and author, United States

Watts, Julia E. "Benefits of Storytelling Methodologies in Fourth- and Fifth-grade Historical Instruction. Thesis. Department of Curriculum and Instruction, East Tennessee State University, 2006. Two hundred twenty-eight fourth- and fifth-grade students in a southern Indiana elementary school participated in the study in which half of the students listened to and participated in oral narratives during their lessons and half were taught with traditional lecture and note-taking instruction. A History Affinity Scale pre- and post-study test showed significant increase in the storytelling group. No changes were shown in the control group.

Myers, Margaret B. "Telling the Stars: A Quantitive Approach to Assessing the Use of Folktales in Science Education." Thesis, Department of Curriculum and Instruction, East Tennessee State University, 2005. Thirty-five hundred students in eight locations in the US were taught scientific concepts about the stars by pairing stories viewed via video of teller Lynn Moroney with science information. A significant increase in positive attitude toward Science was found.

Fuller, Renee. "Story Time: Mind" in OMNI, June, 1980. pp. 22, 119. A psychologist working with severely brain-damaged children with IQ's of 20 and 30 found they were "suddenly able to gain reading comprehension because they were fed stories instead of a disjointed series of facts." She suggests that story comprehension is so basic that it survives severe neurological damage. MacDonald, Margaret Read. Teaching with Story: Classroom Connections to Storytelling. Atlanta: August House, 2013.

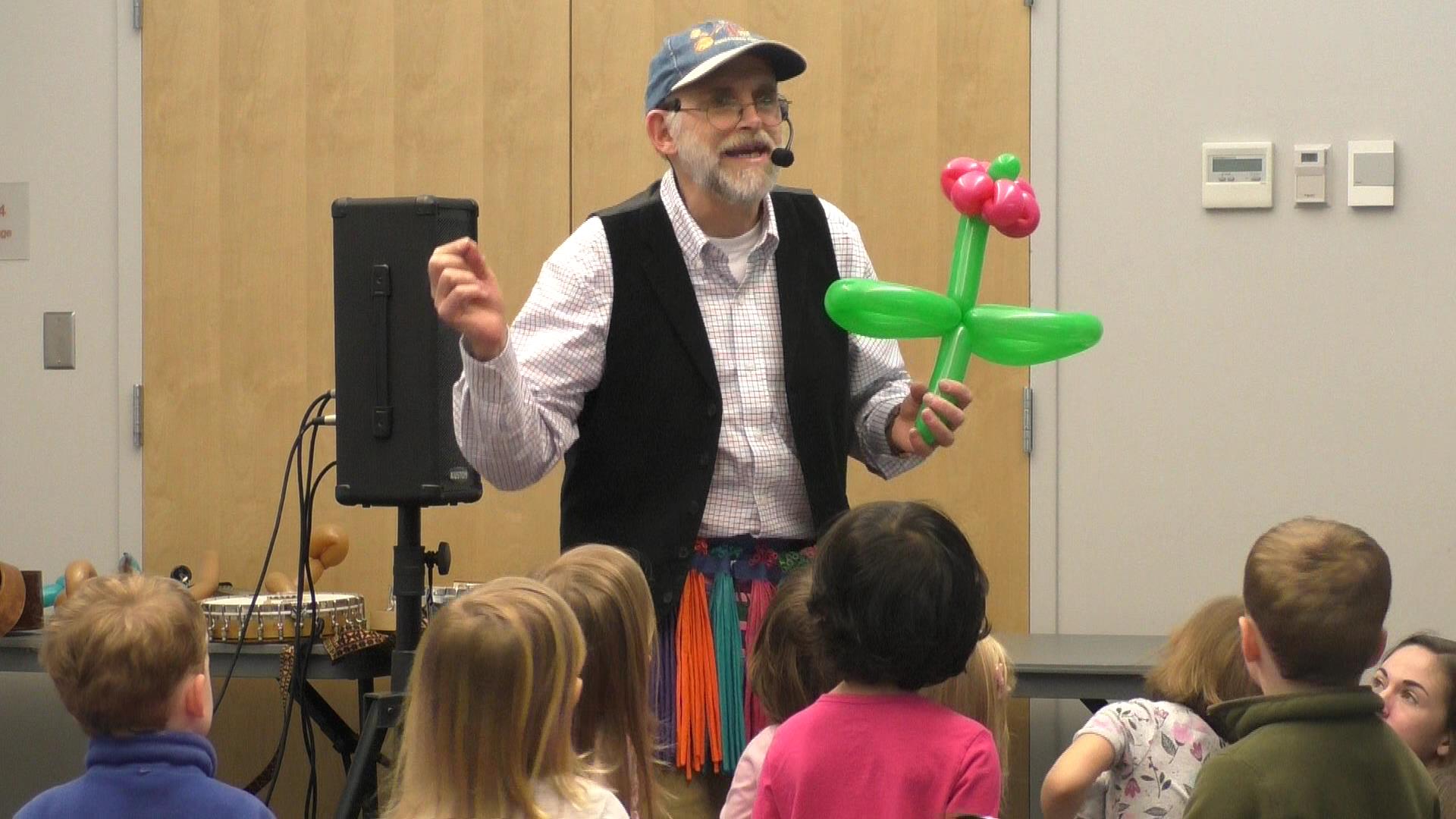

Storytelling Fest 2016 - teller w mask. grassvalleychamber.com

8. GROWING THE IMAGINATION, CREATIVITY & HIGHER ORDER THINKING SKILLS

“When children listen to stories, they respond by creating images of the characters and places described by the words. This process of developing internal images and meaning in response to words is the basis of imagination. Researchers who study brain and behavioral development have identified imagination, not only as the essence of creativity, but as the basis for all higher order thinking. With imagination, with the ability to understand symbols, create solutions, and find meaning in ideas, young people are more capable of mastering language, writing, mathematics, and other learnings that are grounded in the use of symbols.” Fredericks, Linda. “Developing Literacy Skills Through Storytelling.” The Resource Connection, Spring, 1997.

“Intense exposure to stories and storytelling in the classroom stirs and develops the imagination. Storytelling provides imagery-building skills, creates an attentive listener, expands interest into new areas, centers the attention of the class, teaches language, story plots, folkways, ethics, traditions and customs.” What Works About Teaching and Learning, US Department of Education, 1986.

Finnerty, Joyce Carol Powell. "Instruction, imagery, and inference: The effects of three instructional methods on inferential comprehension of elementary children." Ed.D. dissertation, University of Virginia, 1993. During the study 131 second-grade students were given creativity pre- and post-tests. (Thinking creatively in action and movement and early inventory pre-literacy). A storytelling group, a story-reading group, and a control group were used. Both reading-aloud and storytelling groups showed statistically higher creativity scores, but the storytelling group's scores were highest. The increase in creativity scores was especially strong for the lower-socioeconomic students. MacDonald, Margaret Read. Teaching with Story: Classroom Connections to Storytelling. Atlanta: August House, 2013.

"Imagination is a particular kind of flexibility, energy, and vividness that comes from the ability to think of the possible and not just the actual...To be imaginative, then, is not to have a particular function highly developed, but it is to have heightened capacity in all mental functions...It makes mental life more meaningful; it makes life more abundant." Egan, Kieran. Imagination in Teaching and Learning: The Middle School Years. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

9. STORY STRUCTURE & CONTENT ASSIST IN MEMORY

9. STORY STRUCTURE & CONTENT ASSIST IN MEMORY

"Information is remembered better and longer, and recalled more readily and accurately when it is remembered within the context of a story.

“Schank (1990)…[said], “The major processes of memory are the creation, indexing, storage, and retrieval of stories.’ He also stated, ‘We have great difficulty remembering abstract concepts and data. However, we can easily remember a good story….Stories provide tools, context, relevance, and elements readers need in order to understand, remember and index beliefs, concepts and information in the story.’” (Haven, Kendall. Story Proof: The Science Behind the Startling Power of Story. Westport: Libraries Unlimited, 2007. Pg. 71) The work he's citing is "Tell Me a Story" by Roger C. Schank

Based on classroom experiences of tens of thousands of teachers, the National Council of Teachers of English Committee on Storytelling concluded in a 1992 report: “Story is the best vehicle for passing on factual information. Historical figures and events linger in children’s minds when communicated by way of a narrative. The ways of other cultures, both ancient and living, acquire honor in story. The facts about now plants and animals develop, how numbers work, or how government policy influences history – any topic for that matter – can be incorporated into story form and made more memorable.” National Council of Teachers of English, 1992 report.

Jensen, Eric. Teaching with the Brain in Mind. 1998. Jensen explains how memories are stored in various locations in the brain. The more locations a memory is stored in, the greater the likelihood the memory will be retained. He says that storytelling is particularly useful because it connects content with emotion.When students learn something in the context of a story that engages them emotionally, they are more likely to be able to access that learning in the future. MacDonald, Margaret Read. Teaching with Story: Classroom Connections to Storytelling. Atlanta: August House, 2013.

"Sharing stories from various cultures makes geographical knowledge more meaningful. Without them, names and lists of countries may be memorized for test-taking purposes, then quickly forgotten. When connected to story, geographical locations and characteristics are more apt to be remembered." Gangi, Jane M, Associate Professor in the Department of Education at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, CT. Encountering Children’s Literature: An Arts Approach. Pearson (Allyn and Bacon). 2004.

Oaks, Tommy Dale. "A study of storytelling teaching method to positively influence student recall of instruction." Ph.D. dissertation, University of Tennessee, 1995.

One hundred fourteen college students in Instructional Media and Technology courses were divided into two groups. One group was taught via storytelling techniques, the other with traditional methods. A pre-study test, a post-study test done immediately after instruction, and a test given three and five weeks following instruction all showed significantly greater gains in recall by the storytelling group over the control group.

10. STORIES & STORYTELLING INCREASE READING COMPREHENSION

Ray Hicks ncpedi.org

i.gr-assets.com

“Without exception, and without equivocation, research studies conducted over the past quarter century quantify and praise the ability of story structure instruction to improve comprehension. Period. Literally hundreds of studies had substantiated that conclusion.

“Information delivered in story structure is easier for readers and listeners to comprehend—especially when the topic of information is unfamiliar to the receiver. This improved comprehension relates to the familiar structure, greater inclusion of sensory details in story formats, and story’s ability to engage banks of prior topical and structural knowledge in the receiver’s mind.

“Stories provide an additional kind of truth besides scientific fact. This is character truth that creates context, relevance, and empathy for both factual information and for struggles of each character.’ Characters represent surrogate models for the reader and allow the reader to interpret and understand text content. The meaning for facts, data, or concepts does not come from those facts alone. Rather it comes through characters and requires story elements (for example, intention, struggle, conflicts, and reaction) in order to be understood by readers.

"This positive effect of instruction on story structure has been well documented for both good and poor readers and for the comprehension of both stories and expository narratives (Spiegel and Fitzgerald 1986; Buss, Ratcliff, and Irions 1985; Bransford and Stein 1993; Liang and Dole 2006;Snow and Burns 1998; and Griffey et al. 1988). Bruan and Gordon (1983) and Morrow (1983) both concluded that knowledge of story structure strongly impacts comprehension.

"Greenwald and Rossing compared comprehension scores for a test group of third graders who followed a standard basal program with an experimental group that surrounded the same basal stories with instruction on story structure and the core structural elements of a story. ‘Their work with each group significantly outperformed the control group on free recall, guided recall, and retelling post tests’ (Greenwalk and Rossing, 1986).

"They concluded, ‘There is ample research evidence to indicate that children’s knowledge of the structure of stories is critical to comprehension by providing an organizational framework within which Incoming information can be integrated and by providing motivation and encouragement to engage this neural mapping process.’ This conclusion was supported by studies by Mandler and Johnson (!977); Rumelhart (1975); Stein and Glenn (1979); Dreher and Singer (1980); and Sebesta, Calder, and Cleland (1978).” Haven, Kendall. Story Proof: The Science Behind the Startling Power of Story. Westport: Libraries Unlimited, 2007.

Smith, Ward William. "The effects of story presentation strategies on story recall and understanding of fourth graders with different information processing styles." Ed.D. dissertation, United States International University, 1991. Two hundred twenty-two fourth graders were tested to determine their learning styles. Students experienced a story either through storytelling, hearing the teacher read aloud or independent reading. They were given a multiple choice test to test short term memory and a story mapping activity to test long term memory. Students, regardless of their learning styles (learning-sequential, integrated processors, or holistic-global) had better comprehension when experiencing the story through storytelling.

11. STORY-TELLING IS THE MOST IMPACTFUL STORY PRESENTATION FORM

“The Effects of Storytelling versus Story Reading on Comprehension and Vocabulary Knowledge of British Primary School Children”: This article compares effects of storytelling versus story reading on comprehension and vocabulary development of 32 British primary children. States one group listened to stories in storytelling style, the other group listened to stories read by a student teacher. Finds children who witnessed storytelling scored higher on comprehension/vocabulary measures than did children who listened to story reading. Reading Improvement; v35 n3 p127-36 Fall 1998, by Susan Trostle and Sandy Jean Hicks

"A 1999 study showed that 'telling stories to primary-grade students improved their vocabulary faster than did reading to them.' ...Storytelling creates excitement, enthusiasm, and more detailed and expansive images in the mind of the listener than does the same story delivered in other ways.” Haven, Kendall. Story Proof: The Science Behind the Startling Power of Story. Libraries Unlimited, Westport CT, 2007

“Storytelling and Story Reading: A Comparison of Effects on Children’s Memory and Story Comprehension”: A thesis presented to the faculty of the department of Curriculum and Instruction East Tennessee State University by Matthew P. Gallets, May, 2005 (ETSU is the only university in the United States that offers a master’s degree in storytelling.) “The population studied consisted of kindergarten, first, and second grade students. Half the students were read stories aloud, the other half were told the same stories by a storyteller. Students in both the reading and storytelling groups improved on most measures. However, on some measures, notably those regarding recall ability, students in the storytelling group improved more than students in the reading group.”

12. THE ULTIMATE GAIN: STUDENTS TELLING STORIES

“Second grade students at Lowell School, Waterloo, Iowa, were taught storytelling techniques and given opportunities to practice these techniques for 35-40 minutes per week for six months. This activity, held during lunch, was self-selected and conducted in small groups (8-9 students in each group, with 43 students total). …After six months, these students significantly increased their performance on vocabulary and reading comprehension tests beyond what was expected for that six month period, as measured by pre- and post- Iowa Tests of Basic Skills.” The Effects of Storytelling Experiences on Vocabulary Skills of Second Grade Students: A research paper presented to the faculty of the Library Science Department, University of Northern Iowa, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Gail Froyen 1987. Wright, A. Storytelling with children. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

“Second grade students at Lowell School, Waterloo, Iowa, were taught storytelling techniques and given opportunities to practice these techniques for 35-40 minutes per week for six months. This activity, held during lunch, was self-selected and conducted in small groups (8-9 students in each group, with 43 students total). …After six months, these students significantly increased their performance on vocabulary and reading comprehension tests beyond what was expected for that six month period, as measured by pre- and post- Iowa Tests of Basic Skills.” The Effects of Storytelling Experiences on Vocabulary Skills of Second Grade Students: A research paper presented to the faculty of the Library Science Department, University of Northern Iowa, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Gail Froyen 1987. Wright, A. Storytelling with children. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

“Children at any level of schooling who do not feel as competent as their peers in reading or writing are often masterful at storytelling. The comfort zone of the oral tale can be the path by which they reach the written one. Tellers who become very familiar with even one tale by retelling it often, learn that literature carries new meaning with each new encounter. Students working in pairs or in small storytelling groups learn to negotiate the meaning of a tale." Teaching Storytelling: Position Statement from the Committee on Storytelling, National Council of Teachers of English, 1992

"The kids stepped inside those stories and walked around in them - which is what you do, of course, when you're in a story and you're telling it - you experience and internalize it. It was better than any lesson I ever did on rising-action and suspense-building, turning point and denouement. They figured out what makes a story work. They got it, because they stood inside a piece of literature and lived it. Gillard, Marni. Storyteller, Storyteacher: Discovering the Power of Storytelling for Teaching and Living. York, ME: Stenhouse, 1996.

"After the show was over one of the mothers stopped to speak with me. Her son was one of my [intermediate school workshop] tellers three years ago. At the time, he struggled with his reading skills and was receiving extra help. He was a bit shy, not very confident, but he took a leap of faith and joined the storytelling club. He wasn’t the most talented teller but what he lacked in raw talent he made up in effort and enthusiasm. At the Storytelling Festival that year his mother came up to me with tears in her eyes, clutching the folktale book with the story he had just shared on stage. She couldn’t believe the transformation in her child, how storytelling had made such a difference in his confidence level and in his life.

Tonight, again with tears in her eyes, she recalled that evening and told me that he is now a straight A student and loves to read. She urged me to never stop what I was doing and said that I had changed his life. Of course I know it wasn’t me, it was the power of story, but it did my heart so much good to hear how well that kind and gentle boy is faring in his new school …

Karen Chace, storyteller from East Freetown, Masschusetts USA, Storytell email list 29/10/05

13. STORYTELLING HELPS ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND DUAL LANGUAGE LEARNERS

13. STORYTELLING HELPS ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND DUAL LANGUAGE LEARNERS

"When children create and tell a story in their own or a second language, the language becomes theirs." Wright, A. Storytelling with children. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

“Storytelling offers a wonderful way for students who are new to a language to develop their vocabulary and comprehension. It’s a remarkable tool that helps scaffold language for those students who are leaning English in your classroom… Simple folktales .. help students develop both their receptive and productive language skills. When the tales are told in simple language, students not only listen and comprehend, they also find success joining in during the telling and, eventually, retelling the tales on their own. The refrains embedded in many folktales allow for joyful repetition of key phrases. What a joy to learn a new language!” MacDonald, Margaret Read. Teaching with Story: Classroom Connections to Storytelling. Atlanta, GA: August House, 2013.

“I guess I was thinking storytelling would just have entertainment value, but it is really great for all of my readers that range from first-grade/ELL level readers to fifth-grade readers. It gives them equal standing.” Kelly Kennedy, Grade ¾, Adams Elementary School, Seattle, WA. (from Teaching with Story)

“I was truly amazed at my student responses. My groups include speakers from at least ten different languages and twenty different countries. Every one of my ELL students loved hearing and retelling these stories with me. We enjoyed putting motion to the stories and acting them out. Since many of my students enter the classroom in what we ELL teachers call the ‘silent period of language development,’ this really broke the ice for them. Now even my newest ELL students are more able to speak about events in their lives and write them down.” Susan Ramos, ELL 1-4, Challenger Elementary School, Mukilteo, WA.(from Teaching with Story)

14. STORY-LISTENING PREPARES PRESCHOOLERS FOR READING

"Storytelling improves listening comprehension, a vital pre-reading skill for children, introduces us to literature we may not be familiar with, whets our appetite for further literary experiences, introduces us to characters with whom we can relate, has been the best tool for passing on the values and morals of families and peoples for centuries, increases our understanding and awareness of our world’s diverse cultures, develops mental imaging ability, another skill necessary for reading comprehension." Susanna Holstein, Librarian and Storyteller, USA

Students aged 11-14 at Hauppauge Middle School (Long Island, New York) write original stories, learn storytelling techniques, and then tell their stories to preschool children. “Findings show that most of the preschool children read more books, select a wide variety of materials, maintain a desire to read, and tell their own stories. The middle school students increase their sensitivity for communicating with a unique audience and they report an improved awareness of children’s ability to use and appreciate language.” Reading, Writing, and Storytelling: A Bridge from the Middle School to the Preschool”, by Joseph Sanacore and Al Alio, 2007 (no publication source given)

15. CONCLUSION - TEACHING STORYTELLING:

A Position Statement from the Committee on Storytelling, 1992

National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE)

Once upon a time, oral storytelling ruled. It was the medium through which people learned their history, settled their arguments, and came to make sense of the phenomena of their world. Then along came the written word with its mysterious symbols. For a while, only the rich and privileged had access to its wonders. But in time, books, signs, pamphlets, memos, cereal boxes, constitutions—countless kinds of writing appeared everywhere people turned. The ability to read and write now ruled many lands. Oral storytelling, like the simpleminded youngest brother in the olden tales, was foolishly cast aside. Oh, in casual ways people continued to tell each other stories at bedtime, across dinner tables, and around campfires, but the respect for storytelling as a tool of learning was almost forgotten.

Luckily, a few wise librarians, camp counselors, folklorists, and traditional tellers from cultures which still highly valued the oral tale kept storytelling alive. Schoolchildren at the feet of a storyteller sat mesmerized and remembered the stories till the teller came again. Teachers discovered that children could easily recall whatever historical or scientific facts they learned through story. Children realized they made pictures in their minds as they heard stories told, and they kept making pictures even as they read silently to themselves. Just hearing stories made children want to tell and write their own tales. Parents who wanted their children to have a sense of history found eager ears for the kind of story that begins, “When I was little. . . . ” Stories, told simply from mouth to ear, once again traveled the land.

What Is Storytelling?

Storytelling is relating a tale to one or more listeners through voice and gesture. It is not the same as reading a story aloud or reciting a piece from memory or acting out a drama—though it shares common characteristics with these arts. The storyteller looks into the eyes of the audience and together they compose the tale. The storyteller begins to see and re-create, through voice and gesture, a series of mental images; the audience, from the first moment of listening, squints, stares, smiles, leans forward or falls asleep, letting the teller know whether to slow down, speed up, elaborate, or just finish. Each listener, as well as each teller, actually composes a unique set of story images derived from meanings associated with words, gestures, and sounds. The experience can be profound, exercising the thinking and touching the emotions of both teller and listener.

Why Include Storytelling in School?

Everyone who can speak can tell stories. We tell them informally as we relate the mishaps and wonders of our day-to-day lives. We gesture, exaggerate our voices, pause for effect. Listeners lean in and compose the scene of our tale in their minds. Often they are likely to be reminded of a similar tale from their own lives. These naturally learned oral skills can be used and built on in our classrooms in many ways.

Students who search their memories for details about an event as they are telling it orally will later find those details easier to capture in writing. Writing theorists value the rehearsal, or prewriting, stage of composing. Sitting in a circle and swapping personal or fictional tales is one of the best ways to help writers rehearse.

Listeners encounter both familiar and new language patterns through story. They learn new words or new contexts for already familiar words. Those who regularly hear stories, subconsciously acquire familiarity with narrative patterns and begin to predict upcoming events. Both beginning and experienced readers call on their understanding of patterns as they tackle unfamiliar texts. Then they re-create those patterns in both oral and written compositions. Learners who regularly tell stories become aware of how an audience affects a telling, and they carry that awareness into their writing.

Both tellers and listeners find a reflection of themselves in stories. Through the language of symbol, children and adults can act out through a story the fears and understandings not so easily expressed in everyday talk. Story characters represent the best and worst in humans. By exploring story territory orally, we explore ourselves—whether it be through ancient myths and folktales, literary short stories, modern picture books, or poems. Teachers who value a personal understanding of their students can learn much by noting what story a child chooses to tell and how that story is uniquely composed in the telling. Through this same process, teachers can learn a great deal about themselves.

Story is the best vehicle for passing on factual information. Historical figures and events linger in children’s minds when communicated by way of a narrative. The ways of other cultures, both ancient and living, acquire honor in story. The facts about how plants and animals develop, how numbers work, or how government policy influences history—any topic, for that matter—can be incorporated into story form and made more memorable if the listener takes the story to heart.

Children at any level of schooling who do not feel as competent as their peers in reading or writing are often masterful at storytelling. The comfort zone of the oral tale can be the path by which they reach the written one. Tellers who become very familiar with even one tale by retelling it often, learn that literature carries new meaning with each new encounter. Students working in pairs or in small storytelling groups learn to negotiate the meaning of a tale.

How Do You Include Storytelling in School?

Teachers who tell personal stories about their past or present lives model for students the way to recall sensory detail. Listeners can relate the most vivid images from the stories they have heard or tell back a memory the story evokes in them. They can be instructed to observe the natural storytelling taking place around them each day, noting how people use gesture and facial expression, body language, and variety in tone of voice to get the story across.

Stories can also be rehearsed. Again, the teacher’s modeling of a prepared telling can introduce students to the techniques of eye contact, dramatic placement of a character within a scene, use of character voices, and more. If students spend time rehearsing a story, they become comfortable using a variety of techniques. However, it is important to remember that storytelling is communication, from the teller to the audience, not just acting or performing.

Storytellers can draft a story the same way writers draft. Audiotape or videotape recordings can offer the storyteller a chance to be reflective about the process of telling. Listeners can give feedback about where the telling engaged them most. Learning logs kept throughout a storytelling unit allow both teacher and students to write about the thinking that goes into choosing a story, mapping its scenes, coming to know its characters, deciding on detail to include or exclude.

Like writers, student storytellers learn from models. Teachers who tell personal stories or go through the process of learning to tell folk or literary tales make the most credible models. Visiting storytellers or professional tellers on audiotapes or videotapes offer students a variety of styles. Often a community historian or folklorist has a repertoire of local tales. Older students both learn and teach when they take their tales to younger audiences or community agencies. Once you get storytelling going, there is no telling where it will take you.

Oral storytelling is regaining its position of respect in communities where hundreds of people of every age gather together for festivals in celebration of its power. Schools and preservice college courses are gradually giving it curriculum space as well. It is unsurpassed as a tool for learning about ourselves, about the ever-increasing information available to us, and about the thoughts and feelings of others.

The simpleminded youngest brother in olden tales, while disregarded for a while, won the treasure in the end every time. The NCTE Committee on Storytelling invites you to reach for a treasure—the riches of storytelling.

This position statement may be printed, copied, and disseminated without permission from NCTE.